The Two-Hit Hypothesis: Insight from statistics

Quantitative hypotheses that have revolutionaized biology are ubiquitous, but the way the life sciences are taught, it doesn’t always seem that way. I first heard of Knudson’s two hit hypothesis in my Cell Biology class, where it was presented as a core tenet of cancer biology. The Professor failed to mention how Alfred Knudson Jr. arrived at that conclusion.

In 1968, Dr. J.B. Ashley published a collection of data on the incidence of cancers in males and females, and concluded that, after correcting for sex-linked differences and lung cancers caused by disproportionate male smokers, males showed a higher incidence of cancer than females. Hypothesizing about the cause of this sex-linked difference, Ashley claimed hormonal differences, coupled to the stronger female immune system, along with a “difference in physical size” as important reasons.

This was at a time when the nature of cancer and the source of tumorigenesis was being examined, and in the absence of molecular and genetic data, statistics-bsed arguments were being proposed by comparing to patient survival data collected from hospitals. It was known that mutations cause cancer, but there were multiple theories as to the exact requirements in terms of mutations for a successful tumor to form. The next year, he published a paper titled The two *hit” and multiple “hit” theories of carcinogenesis, in which he used statistical arguments to compare previous theories, the Two-hit theory by Armitage and Doll, 1957, and the Multiple-Hit theory by Stocks, 1963 in his analysis of gastric cancer. Using patient mortality data from gastric cancer cases in women, he examined predictions of age-specific death rates in the two contrasting theories, and concluded that

Graphical analysis of the death rates at five year age intervals for gastric cancer in women show a quantitatively and qualitatively better fit with the mathematical expression derived for a multi-stage theory of carcinogenesis than with that derived from a two stage theory.

What he had succeeded in showing was the relationship between the number of mutations and the age pf patient mortality. However, the nature of mutations required for tumor formation in a general cancer context still remained an open question.

Two years later, Knudson published his observations in PNAS in April, 1971 in a paper titled Mutation and Cancer: Statistical Study of Retinoblastoma. He refuted Ashley’s claim about the requirement of 3-7 mutations to cause cancer. Rather he claimed that the requirement for cancer was as little as 2 cancer-causing mutations. For this, Knudson chose retinoblastoma data from the M. D. Anderson Hospital. This cancer is not sex-linked, and there is a high enough incidence in children to rule out purely age-based causes.

Retinoblastoma can either cause tumors in a single eye (unilateral), or in both eyes (bilateral). Using published data, Knudson argued that 55-65% of retinoblastoma cases, more than half of all cases, could be attributed to non-hereditary causes, and all of these cases happened to be unilateral. Next, Knudson examined the incidence of cancer in families known to carry the retinoblastoma, which is reproduced below

| Condition | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Unaffected | 1-10 % |

| Unilateral | 25-40 % |

| Bilateral | 60-75 % |

What stands out is that

- Every carrier of mutation does not exhibit the cancer phenotype

- The incidence of unilateral and bilateral tumors is not equal, indicating a propensity for bilateral tumors.

The distribution of proportions in the three different classes of patients is very conspicuous; the probabilities of 0, 1, or more tumors specifically, form a long tailed distribution, resembling the Poisson distribution. The mean of this Poisson distribution would then give the average of tumors in a population of retinoblastoma patients whose origins is genetic.

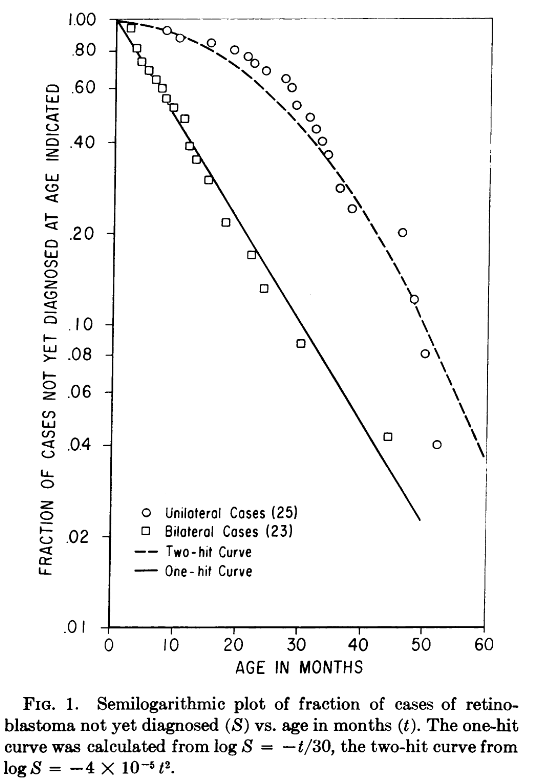

Making some approximate assumptions about the number of retinal cells and comparing the statistics of cacner rates, Knudson was able to make predictions about the distribution of mutations with respect t oage in months assuming either a single tumor-causing mutation, or two independent tumor causing mutation events. The resuls of his analysis are shown here

Voila! The One-Hit curve coincides with the bilateral retinoblastoma data, the hereditary form, indicating that in tissue carrying a genetic mutation, a single new mutation is sufficient in causing cancer. Further, the Two-hit curve coincides with the unilateral retinoblastoma data, which is non-hereditary. Knudson’s reading of this result was that cancercinogenesis require at least two independent mutations. He states:

If a second, single event is involved m the distribution of bilateral cases with time should be an exponential function, i.e., the fraction of the total cases that develops in a given period of time should be constant, as expressed in the relationship $\frac{dS}{dt}=-kS$ … where S is the fraction of survivors not yet diagnosed at time t, and dS is the change in this fraction in the interval dt.

Some comments.

- Knudson discusses various other components of the data used in this analysis, including multiple tumors in each eye, as well as unilateral tumors in patients with familial history of retinoblastoma.

- Why does the assumption of a Poisson distribution work so well?

- In some sense, doesn’t the dataset (retinoblastoma in children) limit the interpretation of his hypothesis? Shouldn’t the conclusion be: carcinogenesis may require a minimum of two-hits for cancers that are not age- or sex-dependent, are independent of metabolic status, or other environmental perturbations. In which case it becomes pretty narrow. Huh.

- It is pretty amazing that it actually worked!