Why are 20nt primers sufficiently unique in the human genome?

I recently came across a neat information theoretic proof of why a primer of length 20nt is pretty much unique in the human genome. I decided to work it out for myself using plain probabilities first.

The problem

Given the genome of size \(N\), how long \(n\) should a primer be to statistically match uniquely in the genome.

You can skip the first section if you want to see the Shannon entropy demonstration of the same idea.

Assumptions:

- The genome is generated randomly from the 4 bases. This is not really true, but I can roll with it for now, ignoring repeat regions.

- The four bases occur with equal probability 0.25. This isn’t very important, and can be easily adapted to genome specific GC content

The straightforward approach - generate all possible oligonucleotides of length n

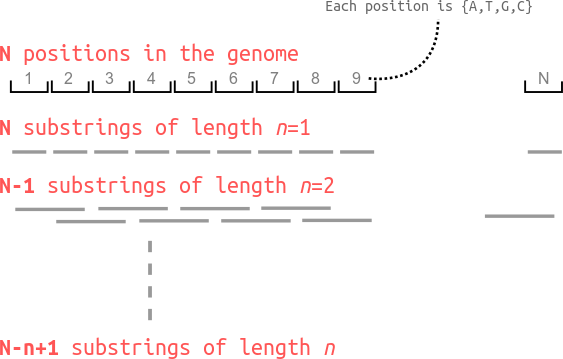

I further assume that all the ‘substrings’ of the genome are independent of each other, the given genome can be split up into smaller contiguous chunks as illustrated below.

.

.

This means I can break up the genome of length N which is hard to think about, into many many “draws” of oligonucleotides of varying lengths.

I am working through this in steps because this is how I convinced myself of this result.

-

What is the totalf number of occurences of a sequence of length n=1. Note: each position can be one of

{A,T,G,C}. From assumption (2) above, for a nucleotide b, its probability of occurence p(b) is 0.25. The total number of occurences can be calculated as the probability of any instance substring of length n=1 times the number of occurences of length n=1 substrings in the genome. I am going to compute these two separately.- There are only 4 unique n=1 mononucleotides possible, namely, “A”, “T”, “G”, “C”. The probability of any one instance of these four occuring is 0.25 (which is p(b) from above).

- The total number of such substrings is p(b)*N because there are N such mononucleotide sequences in the genome.

This tells us that there are N*p(b) occurences of any single one nucleotide string. This makes sense, a quarter of the nucleotides will be the same from assumption (2).

-

Next, what is the total number of occurences of a sequence of length n=2. Now, the possible dinucleotides can be

{AA, AT, AG,....,CC}, i.e. 16 possible dinucleotides. Each of these two positions can be filled independently,- The probability of occurence of any one instance of a dinucleotide is p(b)*p(b) = 0.25*0.25 = 0.0625. (this is the same as 1/16 possible.)

- The genome of length N has N-1 contiguous dinucleotides. See figure above for an illustration of why this is true.

Now, I have (N-1)*p(b)^2 occurences of any dinucleotide sequence.

-

Let me work out one last example, for n=3. The possible trinucleotides are

{AAA, AAT, ..., CCC}, i.e. 4^3 = 64 possible trinucleotides.- The probability of occurence of a given trinucleotide is p(b)*p(b)*p(b) = 0.25^3.

- The number of occurences of contiguous trinucleotides is N-2.

I thus have (N-2)*p(b)^3 occurences of trinucleotides.

I can generalize this pattern now. For a given oligonucleotide of length n, the number of occurences of any particular oligonucleotide in the genome is going to be (N-n+1)*p(b)^n.

Great, but why did I come up with this expression? I wanted to find the length of a primer which is guaranteed to occur exactly once in the genome, which is hopefully our target sequence. I can now solve for this explicitly. I want the number of occurences to be exactly 1.

Solve for n such that:

\[(N-n+1)p(b)^n = 1\]Let us make a quick simplification at this point. I know that typical genomes are massive compared to the size of the primers. I can thus simplify (N-n+1) to N.

\[N p(b)^n = 1 \implies n \log(p(b)) = -\log(N) \implies n = -\log(N)/\log(p(b))\]Lets plug in some values now. If the human genome has length 3e9bp, -log(3*10^9)/log(0.25) = 15.7 which I round up to 16. This result tells us that given our assumptions, any random 16-mer should occur only once in the human genome.

How surprising is to find an oligonucleotide of length n in the human genome?

Claude Shannon’s work on information theory allows us to pose questions like the one above.

The Shannon Entropy allows us to capture the degree of uncertainty in a probability distribution. Alternatively, I think of it as the degree of surprise we expect for any event sampled from a probability distribution. We can thus pose the question, how long must an oligonucleotide sequence be such that it is surprising to find it in the genome?

Shannon Entropy is mathematically defined as \(H_x =- p(x) \log(p(x))\) where p(x) is the probability of occurence of event x.

I am interested in calculating the surprise of occurence of an n length oligomer, which is the sum of entropies of all possible nucleotide states at a given position.

\[H_n =- \Sigma_{i=1}^{n} \Sigma_{b \in \text{ATGC}} p(b) \log(p(b)) = - n (4 p(b) \log(p(b))) = n \log(1/p(b))\](Note: I have cancelled out the 4*p(b) above in this case because p(b)=1/4)

I want to compare this surprise to the random occurence of any length n oligo across the genome. Because of assumption (1) above, any random oligo of any length has an equal chance of occuring anywhere in the genome. For a genome of length N, p(occurence) = 1/N. I denote this with p(o). I can calculate the Shannon Entropy for the (uniform) distribution of motifs of length n across the genome. Here again, I assume that n« N, so I don’t have to be too careful with the summation bounds.

\[H_o = -\Sigma_{i=1}^{N} p(o) \log(p(o)) = -N p(o) \log(p(o)) = -N/N \log(1/N) = \log(N)\]Finally, when does \(H_n \geq H_o\) i.e., the surprise of seeing a random sequence of oligonucleotides exceed the surprise of finding it in the genome?

i.e. \(n \log(1/p(b)) \geq \log(N) \implies n \geq -\log(N)/\log(p(b))\)

This is the same expression as the one above!

It took me a while to convince myself that the above comparison of entropies over two different random variables was OK. One way that I’ve convinced myself is to ask when is the uncertainty of an n length oligonucleotide greater than the uncertainty of finding a random n length sequence anywhere in the genome. I am still not entirely clear what assumptions I might be violating when I compare these two quantities, and I’ll probably post a follow up to this when I learn more.

Takehomes

- The choice of 20nt exceeds the predicted 16nt for the human genome. This essentially guarantees a unique target sequence, as long as we are not looking for repeat regions.

- Both the standard probability based approach and the information theory approach lead to the same result. The second approach however is much more powerful because of its simplicity.

- The general result is that if each letter in an alphabet of size (A) occurs with equal probability, the shortest “word” that will appear at most once in a book of N letters will be given by \(- \log(N)/log(p), p = 1/A\)

- We are interested in the case where the letters don’t all have the same frequency. In this case, the expression will be modified to \(n \geq - \log(N) \frac{1}{\Sigma_{b \in A} p(b) \log p(b)}\). In the case of DNA,

A = {A,T,G,C}, where we can estimate p(A), p(G), p(T), p(C) from the GC content of the genome

I am starting to grok Shannon Entropy and applications of information theory in biology now. I have been thinking about protein and nucleotide motifs and how to test for their statistical significance. There is a whole world of information theory crossed with Markov Models that I am excited to get into!